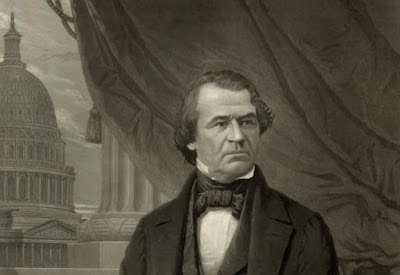

Andrew Johnson Biography - U.S. President (1808–1875) - Andrew Johnson was born in a log lodge in Raleigh, North Carolina, on December 29, 1808. His dad, Jacob Johnson, kicked the bucket when Andrew was 3, leaving the family in destitution. His mom, Mary "Polly" McDonough Johnson, filled in as a sewer to bring home the bacon. She and her second spouse apprenticed Andrew and his sibling, William, to a nearby tailor. As a young man, Andrew felt the sting of partiality from the higher classes and built up a white-supremacist demeanor to adjust, a discernment he held all his life.

Abrading under the limitations of apprenticeship, Johnson and his sibling fled from their commitment. The pair avoided powers who tried to return them to their boss and acted as itinerate tailors. The young men later returned home, and the family moved to Greeneville, Tennessee. In a brief timeframe, Johnson set up an exceptionally effective customizing business and wedded Eliza McCardle in 1827. She empowered him in his self-instruction and guided him on business speculations. Eliza experienced tuberculosis, yet remained a steady supporter of Johnson through their 50-year marriage.

Attack Into Politics

Johnson took a solid enthusiasm for legislative issues, and his tailorshop turned into an asylum for political examination. He picked up the backing of the nearby common laborers and turned into their solid supporter. He was chosen council member in 1829, and was chosen chairman of Greeneville five years after the fact. After the 1831 Nat Turner Rebellion, Tennessee embraced another state constitution with a procurement to disappoint free blacks. Johnson bolstered the procurement and battled around the state for its approval, giving him wide introduction.

In 1835, Johnson won a seat in the Tennessee state assembly. He recognized himself with the Democratic approaches of Andrew Jackson, supporting for poor people and being against insignificant government spending. He was likewise a solid hostile to abolitionist and a promoter of states' rights, while as yet being an unfit supporter of the Union.

U.S. Congressman and Tennessee Governor

In 1843, Johnson turned into the first Democrat from Tennessee to be chosen to the United States Congress. He joined another Democratic greater part in the House of Representatives, announcing that subjection was vital to the safeguarding of the Union. This was a slight takeoff from his kindred Southerners, why should starting talk about partition if subjection was canceled. Amid his fifth and last term in Congress, the Whig gathering was making progress in Tennessee, and Johnson saw that his chances for a 6th term were thin.

In 1853, Johnson was chosen legislative head of Tennessee. Amid his two terms, he attempted to advance his financially moderate, populist sees, yet discovered the experience baffling, as the representative's protected forces were restricted to offering proposals to the lawmaking body, with no veto power. He benefitted as much as possible from his position by giving critical arrangements to political partners.

As the 1856 decision neared, Andrew Johnson quickly considered a keep running for the administration, however felt he didn't have an incredible national introduction he required. He chose to rather keep running for a seat in the U.S. Senate. Despite the fact that his gathering controlled the assembly, the battle was troublesome. Numerous Democratic pioneers objected to his populist sees. Be that as it may, the Tennessee lawmaking body did choose him, and the response by the resistance press was prompt and scorching. The Richmond Whig alluded to Johnson as "the most disgusting radical and most deceitful agitator in the Union."

As representative, Johnson presented the Homestead Act, a bill he had advanced while a congressman. The bill met with solid restriction by numerous Southern Democrats, who dreaded the area would be settled by poor whites and migrants who couldn't bear, or didn't need, servitude in the region. An intensely altered bill was passed, yet was vetoed by President Buchanan. For the rest of his Senate expression, Johnson kept a free course, restricting cancelation while clarifying his commitment to the Union.

The Lincoln Administration

After Abraham Lincoln's race in 1860, Tennessee withdrew from the Union. Andrew Johnson broke with his home state and turned into the main Southern representative to hold his seat in the U.S. Senate. He was denounced in the South. His property was seized, and his wife and two girls were driven out of Tennessee. Be that as it may, his expert Union enthusiasm did not go unnoticed by the Lincoln Administration. When Union troops possessed Tennessee in 1862, Lincoln delegated Johnson military senator. He strolled a troublesome line, offering an olive branch to his kindred Tennesseans while practicing the full constrain of the government to revolts. He was never ready to increase complete control of the state as guerillas, drove by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, assaulted urban communities and towns voluntarily.

Johnson initially contradicted the Emancipation Proclamation, however in the wake of picking up an exclusion for Tennessee and understanding that it was a vital apparatus for completion the war, he acknowledged it. Southern papers got his flip-slumping and blamed him for looking for a higher office. This thought played out when Lincoln, worried about his chances for reelection, tapped Johnson as his VP to adjust the ticket in 1864. After a few prominent Union triumphs in the mid year and fall of 1864, Lincoln was re-chosen in a clearing triumph.

seventeenth President of the United States

On the night of April 14, 1865, while spending a night at Ford's Theater, in Washington, D.C., President Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth, and he kicked the bucket the following morning. Johnson was additionally an objective on that game changing night, yet his eventual professional killer neglected to appear. Three hours after Lincoln kicked the bucket, Andrew Johnson was confirmed as the seventeenth president of the United States. In a peculiar incongruity frequently found in American history, the bigot Southerner Johnson was accused of the recreation of the South and the augmentation of social liberties and suffrage to previous dark slaves. It rapidly got to be evident that Johnson would not drive Southern states to allow full correspondence to blacks, subsequently setting up an encounter with congressional Republicans who looked for dark suffrage as vital to promoting their political impact in the South.

Congress was in break the initial eight months of Andrew Johnson's term, and he exploited the lawmakers' nonappearance by pushing through his own particular Reconstruction arrangements. He immediately issued absolves and absolution to any radicals who might take a vow of constancy. This brought about numerous previous Confederates being chosen to office in Southern states and founding "dark codes," which basically looked after servitude. Later, he extended his absolutions to incorporate Confederate authorities of the most noteworthy rank, including Alexander Stephens, who had served as VP under Jefferson Davis.

At the point when Congress reconvened, individuals communicated insult at the president's mercy requests and his absence of ensuring dark social liberties. In 1866, Congress passed the Freedmen's Bureau bill, giving essentials to previous slaves and assurance of their rights in court. They then passed the Civil Rights Act, characterizing "all persons conceived in the United States and not subject to any outside force, barring Indians not saddled," as residents. Johnson vetoed these two measures on the grounds that he felt that Southern states were not spoke to in Congress and trusted that setting suffrage arrangement was the obligation of the states, not the central government. Both vetoes were overridden by Congress.

That June, Congress affirmed the fourteenth Amendment and issued it to the states for confirmation, and it was acknowledged under one month later. In a novel translation of the "prompt and assent" statement of the Constitution, Congress likewise passed the Tenure of Office Act, which denied the president the ability to evacuate government authorities without the Senate's endorsement. In 1867, Congress set up military Reconstruction in the previous Confederate states to authorize political and social rights for Southern blacks.

President Johnson countered by engaging straightforwardly to the general population in a progression of talks amid the 1866 congressional races. Over and over, it created the impression that Johnson had an excessive amount to drink, and estranged more than persuaded his groups of onlookers. The crusade was a finished catastrophe, and Johnson confronted a further loss of backing from people in general. The Radical Republicans won a mind-boggling triumph in the midterm decisions.

Johnson felt his position as president disintegrating underneath him. He had lost the backing of Congress and the general population, and felt that his just option was to challenge the Tenure of Office Act as an immediate infringement of his protected power. In August 1867, he let go Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, with whom he'd had a few meetings. In February 1868, the House voted to indict President Johnson for infringement of the Tenure of Office Act, and for bringing disfavor and criticism on Congress. He was attempted in the Senate and absolved by one vote. He remained president, however both his validity and viability were obliterated.

Later Years and Legacy

Johnson completed his term keeping up his restriction to Reconstruction and proceeding with his willful part as defender of the white race. In the wake of going out, he exploited his brilliant speech abilities and went on the talking circuit. In 1874, he won race to the U.S. Senate for a brief moment time. In his first discourse subsequent to coming back to the Senate, he stood up contrary to President Ulysses S. Stipend's military mediation in Louisiana. Amid the Congressional break the accompanying summer, Johnson kicked the bucket from a stroke close Elizabethton, Tennessee, on July 31, 1875. As per his wishes, he was covered simply outside Greeneville, his body wrapped in an American banner and a duplicate of the Constitution set under his head.

Attack Into Politics

Johnson took a solid enthusiasm for legislative issues, and his tailorshop turned into an asylum for political examination. He picked up the backing of the nearby common laborers and turned into their solid supporter. He was chosen council member in 1829, and was chosen chairman of Greeneville five years after the fact. After the 1831 Nat Turner Rebellion, Tennessee embraced another state constitution with a procurement to disappoint free blacks. Johnson bolstered the procurement and battled around the state for its approval, giving him wide introduction.

In 1835, Johnson won a seat in the Tennessee state assembly. He recognized himself with the Democratic approaches of Andrew Jackson, supporting for poor people and being against insignificant government spending. He was likewise a solid hostile to abolitionist and a promoter of states' rights, while as yet being an unfit supporter of the Union.

U.S. Congressman and Tennessee Governor

In 1843, Johnson turned into the first Democrat from Tennessee to be chosen to the United States Congress. He joined another Democratic greater part in the House of Representatives, announcing that subjection was vital to the safeguarding of the Union. This was a slight takeoff from his kindred Southerners, why should starting talk about partition if subjection was canceled. Amid his fifth and last term in Congress, the Whig gathering was making progress in Tennessee, and Johnson saw that his chances for a 6th term were thin.

In 1853, Johnson was chosen legislative head of Tennessee. Amid his two terms, he attempted to advance his financially moderate, populist sees, yet discovered the experience baffling, as the representative's protected forces were restricted to offering proposals to the lawmaking body, with no veto power. He benefitted as much as possible from his position by giving critical arrangements to political partners.

As the 1856 decision neared, Andrew Johnson quickly considered a keep running for the administration, however felt he didn't have an incredible national introduction he required. He chose to rather keep running for a seat in the U.S. Senate. Despite the fact that his gathering controlled the assembly, the battle was troublesome. Numerous Democratic pioneers objected to his populist sees. Be that as it may, the Tennessee lawmaking body did choose him, and the response by the resistance press was prompt and scorching. The Richmond Whig alluded to Johnson as "the most disgusting radical and most deceitful agitator in the Union."

As representative, Johnson presented the Homestead Act, a bill he had advanced while a congressman. The bill met with solid restriction by numerous Southern Democrats, who dreaded the area would be settled by poor whites and migrants who couldn't bear, or didn't need, servitude in the region. An intensely altered bill was passed, yet was vetoed by President Buchanan. For the rest of his Senate expression, Johnson kept a free course, restricting cancelation while clarifying his commitment to the Union.

The Lincoln Administration

After Abraham Lincoln's race in 1860, Tennessee withdrew from the Union. Andrew Johnson broke with his home state and turned into the main Southern representative to hold his seat in the U.S. Senate. He was denounced in the South. His property was seized, and his wife and two girls were driven out of Tennessee. Be that as it may, his expert Union enthusiasm did not go unnoticed by the Lincoln Administration. When Union troops possessed Tennessee in 1862, Lincoln delegated Johnson military senator. He strolled a troublesome line, offering an olive branch to his kindred Tennesseans while practicing the full constrain of the government to revolts. He was never ready to increase complete control of the state as guerillas, drove by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, assaulted urban communities and towns voluntarily.

Johnson initially contradicted the Emancipation Proclamation, however in the wake of picking up an exclusion for Tennessee and understanding that it was a vital apparatus for completion the war, he acknowledged it. Southern papers got his flip-slumping and blamed him for looking for a higher office. This thought played out when Lincoln, worried about his chances for reelection, tapped Johnson as his VP to adjust the ticket in 1864. After a few prominent Union triumphs in the mid year and fall of 1864, Lincoln was re-chosen in a clearing triumph.

seventeenth President of the United States

On the night of April 14, 1865, while spending a night at Ford's Theater, in Washington, D.C., President Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth, and he kicked the bucket the following morning. Johnson was additionally an objective on that game changing night, yet his eventual professional killer neglected to appear. Three hours after Lincoln kicked the bucket, Andrew Johnson was confirmed as the seventeenth president of the United States. In a peculiar incongruity frequently found in American history, the bigot Southerner Johnson was accused of the recreation of the South and the augmentation of social liberties and suffrage to previous dark slaves. It rapidly got to be evident that Johnson would not drive Southern states to allow full correspondence to blacks, subsequently setting up an encounter with congressional Republicans who looked for dark suffrage as vital to promoting their political impact in the South.

Congress was in break the initial eight months of Andrew Johnson's term, and he exploited the lawmakers' nonappearance by pushing through his own particular Reconstruction arrangements. He immediately issued absolves and absolution to any radicals who might take a vow of constancy. This brought about numerous previous Confederates being chosen to office in Southern states and founding "dark codes," which basically looked after servitude. Later, he extended his absolutions to incorporate Confederate authorities of the most noteworthy rank, including Alexander Stephens, who had served as VP under Jefferson Davis.

At the point when Congress reconvened, individuals communicated insult at the president's mercy requests and his absence of ensuring dark social liberties. In 1866, Congress passed the Freedmen's Bureau bill, giving essentials to previous slaves and assurance of their rights in court. They then passed the Civil Rights Act, characterizing "all persons conceived in the United States and not subject to any outside force, barring Indians not saddled," as residents. Johnson vetoed these two measures on the grounds that he felt that Southern states were not spoke to in Congress and trusted that setting suffrage arrangement was the obligation of the states, not the central government. Both vetoes were overridden by Congress.

That June, Congress affirmed the fourteenth Amendment and issued it to the states for confirmation, and it was acknowledged under one month later. In a novel translation of the "prompt and assent" statement of the Constitution, Congress likewise passed the Tenure of Office Act, which denied the president the ability to evacuate government authorities without the Senate's endorsement. In 1867, Congress set up military Reconstruction in the previous Confederate states to authorize political and social rights for Southern blacks.

President Johnson countered by engaging straightforwardly to the general population in a progression of talks amid the 1866 congressional races. Over and over, it created the impression that Johnson had an excessive amount to drink, and estranged more than persuaded his groups of onlookers. The crusade was a finished catastrophe, and Johnson confronted a further loss of backing from people in general. The Radical Republicans won a mind-boggling triumph in the midterm decisions.

Johnson felt his position as president disintegrating underneath him. He had lost the backing of Congress and the general population, and felt that his just option was to challenge the Tenure of Office Act as an immediate infringement of his protected power. In August 1867, he let go Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, with whom he'd had a few meetings. In February 1868, the House voted to indict President Johnson for infringement of the Tenure of Office Act, and for bringing disfavor and criticism on Congress. He was attempted in the Senate and absolved by one vote. He remained president, however both his validity and viability were obliterated.

Later Years and Legacy

Johnson completed his term keeping up his restriction to Reconstruction and proceeding with his willful part as defender of the white race. In the wake of going out, he exploited his brilliant speech abilities and went on the talking circuit. In 1874, he won race to the U.S. Senate for a brief moment time. In his first discourse subsequent to coming back to the Senate, he stood up contrary to President Ulysses S. Stipend's military mediation in Louisiana. Amid the Congressional break the accompanying summer, Johnson kicked the bucket from a stroke close Elizabethton, Tennessee, on July 31, 1875. As per his wishes, he was covered simply outside Greeneville, his body wrapped in an American banner and a duplicate of the Constitution set under his head.

0 Response to "Andrew Johnson Biography - U.S. President (1808–1875)"

Post a Comment